The economic advantage of local 3D printing does not lie in the unit cost of the part, but in the near-total elimination of your production line’s downtime costs.

- The Total Downtime Cost (TDC) of a machine waiting for an imported part often exceeds the cost of a quick local print by several thousand dollars.

- Local additive manufacturing gives you operational sovereignty, freeing you from dependence on single suppliers and fragile supply chains.

Recommendation: Audit your inventory now to identify non-critical parts in stock whose failure would cause a major shutdown, and evaluate their 3D printing potential.

As a maintenance manager, you know this scenario by heart. A critical machine breaks down. The spare part—a simple gear or a specific bracket—is not in stock. The supplier is in Europe or Asia, and the announced lead time is four to six weeks, not counting customs delays at the Port of Montreal. Every day of waiting translates into thousands of dollars in lost production. Your management asks for accountability, and the only answer you have is: “We’re waiting for delivery.” This costly and frustrating situation is a reality in many Quebec factories.

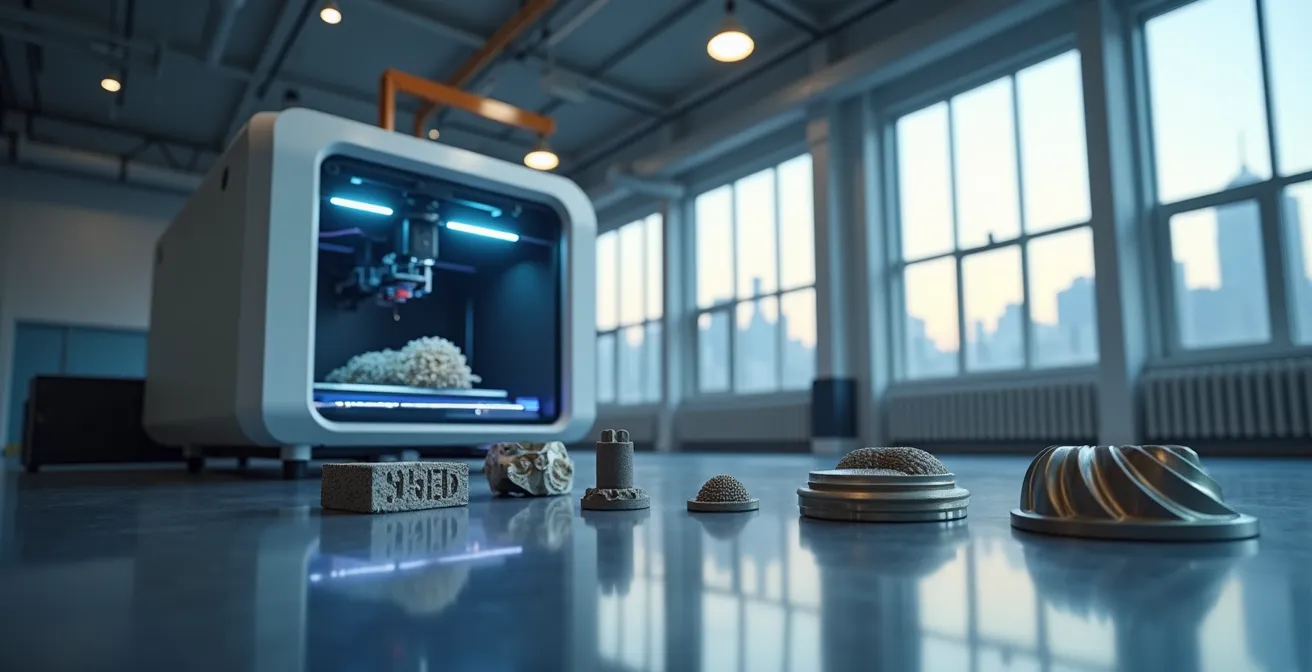

Faced with this, the conventional solution has long been to over-stock parts “just in case,” tying up significant capital in dormant inventory, or paying fortunes in air freight for emergencies. But what if the real issue wasn’t managing logistics better, but breaking free from it? Industrial 3D printing, often perceived as a prototyping tool, is actually a powerful production and maintenance strategy. Calculating its profitability is not limited to comparing the purchase price of an imported part to that of a printed part.

The true economic analysis integrates a factor that many ignore: the Total Downtime Cost (TDC). It is this calculation that shifts the perspective and demonstrates that producing a part locally, even at a higher manufacturing cost, represents a substantial saving for the company. This article aims to provide you, as an application engineer, with the methodology and concrete data to evaluate this opportunity. We will analyze which parts are good candidates, which materials can withstand your industrial constraints, and how to manage risks to transform your maintenance into a strategic advantage.

To guide you through this strategic process, this article is structured to answer the concrete questions you are asking. Each section addresses a key aspect, from identifying opportunities to managing risk, to enable you to make informed decisions.

Summary: Additive manufacturing as a profitability lever for maintenance in Montreal

- How to identify which parts of your inventory are profitable to print?

- Metal, nylon, or resin: which filament resists your factory’s conditions?

- Do you have the right to scan and print a broken patented part?

- The risk of a printed part breaking under load and injuring an employee

- When to schedule sanding and curing stages to avoid delaying the repair?

- Why paying 5x the maritime price is sometimes the smartest saving?

- Why is your 3D printed prototype impossible to mold industrially?

- How to integrate eco-design to reduce your material and packaging costs?

How to identify which parts of your inventory are profitable to print?

The first step toward a profitable additive manufacturing strategy is not to print everything that breaks, but to conduct a strategic analysis of your inventory. The goal is to target parts where 3D printing generates the most value—not in production cost, but in operational gain. The key is to evaluate each part along two axes: its downtime cost (the TDC) and its geometric complexity. Ideal candidates are often parts whose failure shuts down an entire production line, which are difficult to obtain quickly (single supplier, long lead times), and whose shape lends itself well to printing (internal geometries, undercuts).

For older equipment where CAD plans no longer exist, the modeling barrier is no longer an obstacle. Montreal-based companies like Lezar3D specialize in the 3D scanning of existing parts. This “CAD-less” approach allows for the creation of a “digital part heritage”: a library of 3D files of your machine park, ready to be used to print a part on demand. This is insurance against obsolescence and a fundamental step toward agile and autonomous maintenance.

Your action plan for identifying profitable parts to print

- Calculation of Total Downtime Cost (TDC): List direct costs (wages of inactive operators at the average Quebec rate of $35-45/hr) and indirect costs (production loss, late penalties) for each day of machine downtime.

- Logistical Criticality Assessment: Assign a score to each part. Add 10 points per week of standard import delay and an additional 20 points if the part comes from a single supplier with no alternative.

- Geometric Complexity Analysis: Prioritize parts that are difficult or expensive to machine traditionally. Geometries with internal channels, lightweight lattices, or organic shapes are excellent candidates for additive manufacturing.

- Material Availability Check: Confirm with Quebec distributors that the required material (high-performance polymer, metal, etc.) is available locally to ensure rapid production.

- Decision Threshold: Compare the TDC with the printing cost. If the TDC over the import duration exceeds $3,000 or if the supply lead time is greater than 4 weeks, local 3D printing becomes an economically highly advantageous option.

By applying this matrix, you are no longer choosing parts at random, but building a data-driven case to justify the investment in a locally printed part.

Metal, nylon, or resin: which filament resists your factory’s conditions?

Once a candidate part is identified, the choice of material is the most critical step. A spare part must equal or even surpass the performance of the original in terms of mechanical, thermal, and chemical resistance. The range of materials available for industrial 3D printing has expanded considerably, going far beyond prototyping plastics. Today, we find high-performance polymers and metals capable of meeting the most severe requirements.

The choice depends entirely on the application. A part for the food processing sector will need to be made of food-grade certified PA12, while a component for the aerospace industry (such as at Bombardier) will require PEEK for its resistance to hydraulic fluids. The key is not to choose a material based on its cost, but based on its suitability for the constraints of the production environment. A rigorous analysis of Technical Data Sheets (TDS) is essential to validate points such as Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT), tensile strength, and chemical compatibility.

The following table, contextualized for industrial applications present in Quebec, provides an overview of the possible options.

| Material | Industrial Application | Key Resistance | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEEK | Aerospace (Bombardier) | Hydraulic fluids | High |

| ULTEM | Transport (Alstom) | Vibrations/Heat | Medium-High |

| Nylon-CF (Carbon Fiber) | General Manufacturing (tooling, jigs) | Corrosion/Weight | Medium |

| PA12 (SLS) | Food Processing | Food Grade | Medium |

| Maraging Steel | Industrial Tooling (mold inserts) | Extreme Wear | Very High |

Collaborating with a local 3D printing service that has expertise in these materials is a guarantee of safety. They can advise you and ensure that the printing process is optimized for the chosen material.

Do you have the right to scan and print a broken patented part?

The issue of intellectual property is a legitimate concern for any maintenance manager considering 3D printing spare parts. The answer, particularly in the Canadian context, rests on an important nuance: the difference between repair and reconstruction. As a legal analysis by La GBD on the subject points out:

The presiding principle in this matter is that repair is authorized, but within the limit of reconstructing the patented product.

– La GBD – Legal Guide, The protection of 3D printing in intellectual property

Clearly, replacing a worn or broken component of a machine you own is generally considered a legitimate right to repair. You are not recreating the entire machine; you are maintaining it in working order. The situation becomes complicated if you print the part to sell it, or if you print all the components to assemble a new machine, which would constitute infringement. For strict internal maintenance use, the risk is therefore limited, especially if the original manufacturer no longer exists or no longer provides the part.

To act with due diligence, particularly in Canada, it is recommended to follow a structured approach:

- Check Patent Status: Consult the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) database to see if the part or machine is protected by a patent still in force.

- Examine Purchase Contracts: Review the original equipment purchase contract. Some clauses may specifically prohibit or regulate repair using non-official parts.

- Document Internal Use: Keep clear traceability indicating that the part was printed for internal repair and not for commercialization.

- Keep Proof: If the manufacturer no longer exists, keep a record of your attempts to obtain the part through official channels. This demonstrates your good faith.

- Consult in Case of Doubt: For very high-value parts or complex cases, the advice of an attorney specializing in intellectual property is a wise investment.

By respecting these principles, you can integrate additive manufacturing into your maintenance strategy while minimizing legal risks.

The risk of a printed part breaking under load and injuring an employee

A maintenance manager’s greatest fear is the failure of a part, whether it is original or printed. If a 3D-printed spare part fails and causes a workplace accident, the employer’s liability is directly engaged. In Quebec, the CNESST (Commission des normes, de l’équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail) strictly regulates employer obligations. A breach can lead to very heavy financial consequences, far beyond the cost of the part itself.

As specified by the CNESST, as an employer, you have the obligation to take the necessary measures to protect the health and ensure the safety of your workers. In the context of additive manufacturing, this translates into a duty of rigorous diligence. It is not enough to print and install; you must validate and document the part’s performance. The risk of failure must be actively managed, which implies a serious engineering approach. Ignoring this step exposes the company to sanctions that can include significant fines and a drastic increase in premiums.

The solution is not to avoid 3D printing, but to approach it with the same rigor as any other manufacturing method. This involves several key steps:

- Controlled Over-engineering: Use Finite Element Analysis (FEA) software to virtually test the part under the real loads it will undergo. It is often wise to reinforce critical stress zones, even if it means using more material than the original.

- Destructive Testing: For the most critical parts, print multiple copies. Test one to failure in a controlled environment to know its real limit and validate a sufficient safety margin.

- Documentation and Traceability: Maintain a complete file for each printed critical part: material used, printing parameters, simulation results, and test data. This documentation is your best defense in the event of an incident.

- Team Training: Ensure that operators are trained to recognize signs of wear or potential failure in these new parts.

By adopting a methodical and documented approach, you transform a potential risk into a controlled, reliable, and safe maintenance process.

When to schedule sanding and curing stages to avoid delaying the repair?

One of the main arguments in favor of 3D printing is speed. However, it is crucial to have a realistic view of the full process. For many industrial applications, the part that comes out of the printer is not the final part. It must often go through one or more post-processing stages to achieve the required mechanical properties and surface finish. Ignoring these delays in your planning can cancel out some of the expected time savings.

The type of post-processing depends entirely on the printing technology and material used. A metal part printed by Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) will need heat treatment to relax internal stresses, while a resin part (SLA) will require alcohol cleaning and UV post-curing. These steps are non-negotiable and guarantee the part’s performance and durability. Despite these steps, 3D printing can allow for a reduction in assemblies thanks to complex monobloc parts, offering substantial savings.

It is therefore imperative to integrate these delays into the total repair duration calculation. The following table gives an estimate of average lead times for common post-processing available through specialized services in the Montreal area.

| Type of Post-processing | Technology | Average Lead Time | Cost Impact (+%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sanding / Bead Blasting | FDM/SLS/Metal | 24-48h | +15-25% |

| Curing / Debinding | Metal (Binder Jetting) | 48-72h | +30-50% |

| CNC Finish Machining | All | 8-24h | +40-60% |

| Heat Treatment | Metal (DMLS) | 24-48h | +20-30% |

| Polishing / Painting | FDM/SLA | 24h | +20-35% |

The best approach is to discuss the full process with your 3D printing partner from the beginning. A competent engineering service will provide you with a quote and a schedule that includes all necessary steps, giving you a clear and reliable vision of the total time before you can install the part.

Why paying 5x the maritime price is sometimes the smartest saving?

This is where the maintenance cost paradigm shifts. Comparing the purchase cost of a part imported by ship (e.g., $300) to that of a part printed locally (e.g., $2,500) is a fundamental analytical error. This comparison omits the most important cost: that of inactivity. The true profitability calculation must integrate the Total Downtime Cost (TDC), which represents the value lost by the company every day the machine is idle.

This concept of “spare parts on demand” is an industrial revolution. It limits dependence on suppliers, gives new life to equipment whose parts are no longer sourceable, and above all, reduces dormant stock. This is an approach that aligns perfectly with the objectives of industrial sovereignty and supply chain resilience, which are major issues for the Quebec economy.

The following comparative analysis, based on a realistic scenario for a critical part, perfectly illustrates this change in perspective. We start with a TDC estimated at $600/day of shutdown (a very conservative cost).

| Option | Part Cost | Lead Time | TDC (Production Halt) | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maritime Asia | $300 | 6 weeks (42 days) | $25,200 | $25,500 |

| Air Freight YUL | $1,500 | 4 days | $2,400 | $3,900 |

| Montreal 3D Printing | $2,500 | 3 days | $1,800 | $4,300 |

In this scenario, air freight seems slightly more advantageous. However, local 3D printing offers a non-quantifiable but strategic advantage: operational sovereignty. You are no longer at the mercy of a delayed flight, a strike, or a customs blockage. You regain total control over your maintenance chain. Paying $4,300 to avoid a loss of $25,500 is not an expense; it is a saving of more than $21,000.

Why is your 3D printed prototype impossible to mold industrially?

A frequent confusion is the belief that a part designed for 3D printing can be directly used as a model for mass manufacturing by injection molding. This is a technical error that can be costly in terms of redesign. The two manufacturing processes obey radically different Design for Manufacturing (DFM) rules. 3D printing is an additive technology, while molding is essentially a subtractive technology (filling a cavity).

The geometric freedom of 3D printing allows for the creation of shapes unthinkable for molding. For example, complex internal cooling channels, lattice structures to lighten the part, or deep undercuts. These elements, which optimize the performance of the printed part, make it physically impossible to demold. A part intended for molding must imperatively include draft angles, avoid undercuts not managed by complex slides, and have uniform wall thicknesses to avoid sink marks.

3D printing is therefore perfectly suited for the production of spare parts in small and medium series, where the cost of a mold would be prohibitive. The break-even point to justify creating an industrial mold is often beyond several tens or even hundreds of thousands of parts. For maintenance, where one, ten, or fifty parts are needed, 3D printing remains the most economically viable solution.

The key is therefore to choose the right technology for the right use: 3D printing for repair and small series on demand, and molding for mass production of hundreds of thousands of identical parts.

Key Takeaways

- The true indicator of profitability is your equipment’s Total Downtime Cost (TDC), which almost always eclipses the manufacturing cost of the part.

- Local additive manufacturing gives you “operational sovereignty,” protecting you from the disruptions and unpredictable delays of global supply chains.

- The success of a 3D printing maintenance strategy rests on rigorous analysis: identifying the right parts, choosing the appropriate material, and documenting safety tests.

How to integrate eco-design to reduce your material and packaging costs?

Beyond operational profitability, additive manufacturing opens interesting perspectives for sustainability and direct cost reduction. Eco-design is not just an ethical approach; it is an economic optimization lever. Unlike subtractive methods like machining, where a large portion of the raw material is removed and becomes waste, 3D printing uses only the material strictly necessary to build the part. For example, a study shows that material loss in metal casting is around 50%, whereas it is near zero with additive techniques.

This optimization goes further thanks to modern design tools. By using advanced CAD techniques like topological optimization or generative design, it is possible to entirely rethink a part’s structure. The software, based on applied load constraints, calculates the ideal distribution of material, removing everything that is not structurally necessary. The result is a part that is often organic-looking, lighter but just as, if not more, rigid than the original. Studies show that parts are both lighter (typically by 25% to 50%) and more rigid.

This weight reduction translates directly into lower material costs, especially for metals or high-performance polymers. In Quebec, this approach fits into a circular economy logic. Using recycled filaments (such as PETG from bottles) or locally produced bioplastics (such as PLA) reduces not only the cost but also the carbon footprint associated with the transport of raw materials. Programs like the Fonds Écoleader can even financially support companies that adopt these innovative and responsible practices.

Integrating 3D printing into your maintenance strategy is therefore not just a way to reduce your production losses; it is an opportunity to manufacture higher-performance parts, spend less on materials, and strengthen your company’s roots in Quebec’s sustainable industrial ecosystem. To put these tips into practice, the next step is to conduct a criticality audit of your spare parts.